Just as they have done for 17 centuries, the Greek Orthodox monks of St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai desert and the local Jabaliya Bedouins worked together to protect the monastery when the 2011 revolution thrust Egypt into a period of uncertainty. “There was a period in the early days of the Arab Spring when we had no idea what was going to happen,” says Father Justin, a monk who has lived at St. Catherine’s since 1996. Afraid they could be attacked by Islamic extremists or bandits in the relatively lawless expanse of desert, the 25 monks put the monastery’s most valuable manuscripts in the building’s storage room. Their Bedouin friends, who live at the base of Saint Catherine’s in a town of the same name, allegedly took up their weapons and guarded the perimeter.

Just as they have done for 17 centuries, the Greek Orthodox monks of St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai desert and the local Jabaliya Bedouins worked together to protect the monastery when the 2011 revolution thrust Egypt into a period of uncertainty. “There was a period in the early days of the Arab Spring when we had no idea what was going to happen,” says Father Justin, a monk who has lived at St. Catherine’s since 1996. Afraid they could be attacked by Islamic extremists or bandits in the relatively lawless expanse of desert, the 25 monks put the monastery’s most valuable manuscripts in the building’s storage room. Their Bedouin friends, who live at the base of Saint Catherine’s in a town of the same name, allegedly took up their weapons and guarded the perimeter.

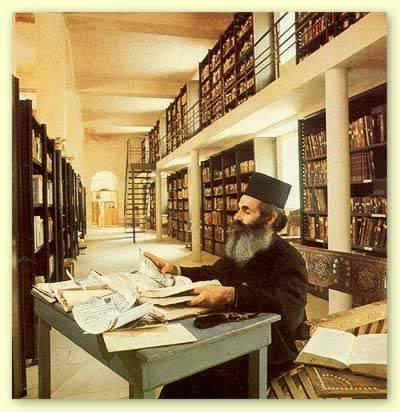

The community’s fears of an attack were not realized, but the monks decided they needed a new way to protect their treasured library from any future threats. Last year, they began a program of digitally copying biblical scripts with the help of multispectral imaging specialists from around the world, while simultaneously renovating and modernizing the library itself. The Sinai library houses 1.8 million pages of script, including essential texts that document the early church. St. Catherine’s ranks high among the world’s preeminent Christian text collections: their Greek manuscripts are second in number only to the Vatican’s and their hallmark Arabic and Turkish scrolls document the interaction between the monastery and the surrounding world of Islam over the centuries. The monastery’s project will create a digital library for scholars around the world. “The technology, the conservation — they are our protection. Many people are concerned about the safety of what we have here, so we have to make them sure that we are protecting our materials and appreciating our responsibility,” says Father Justin, the monastery’s librarian.

Security concerns are once again at the forefront after the July 3 military ouster of former President Mohamed Morsi and the violence that came in the wake of the change in the country’s leadership. Two days after Morsi’s ouster, the Egyptian army declared a state of emergency in Sinai after Islamist gunmen opened fire on the region’s el-Arish airport and several military checkpoints, killing several police officers and a soldier. St. Catherine’s is geographically vulnerable at the best of times, positioned as it is on a peninsula plagued by a security vacuum. Crimes like human trafficking and kidnappings along the Egypt-Israel border make Sinai one of Egypt’s most dangerous regions.

Father Justin acknowledges that the conservation efforts have been inspired by neighborhood insecurity. “Libraries are precious places where you can store the past in the present, and we are treating what happened to Cairo” — the riots, looting and violence that surrounded the revolution — “as a reminder that libraries are vulnerable, and right now they are more vulnerable than ever,” he says, sitting in his no-frills office in front of a MacBook Pro. He politely steps out to a dark room every few minutes to turn the page of an ancient manuscript so that an imaging crew from Greece can scan the palimpsest.

The two-plus years since the toppling of former President Hosni Mubarak have been unsettling for Egypt’s Christians, the majority of whom belong to the Coptic Church and account for a significant minority (up to 10%) of the country’s population. There have been violent clashes between Christians and Muslims, with deaths on both sides. St. Catherine’s has nevertheless maintained its track record of friendly relationships with its Muslim neighbors. The Greek Orthodox monks and the Jabaliya Bedouin tribe, who are the area’s majority residents, have shared land, food and friendly relations since the monastery was built centuries ago. The Jabaliya are believed to be descendants of the Byzantine soldiers who built the monastery in the 6th century, and many of them continue to guard the monastery as their own. “The monastery is a very special place for me and all Bedouins. It is a holy place for all religions. Our ancestors built St. Catherine’s,” explains Ramadan, 26, who has been a tour guide at the monastery since he was 15.

Another Bedouin resident, Faraj, just out of Friday morning prayers at a nearby mosque, adds: “[The Jabaliya and the monks] have been here for so long that we have grown together. We’ve been through times when we had to share our food and gardens. We share everything, we always have. There is even a mosque on the monastery. We don’t use it often anymore because our population is too big now, but it is a still a symbol of our friendly relationship.”

Eager to maintain similarly peaceful relations with all Egyptians, the monks hope their ongoing project will act as a reminder of the monastery’s historical bond with Egypt. “We have to present ourselves in a way to convince the Arabic-speaking world that we are a part of Egypt’s ancient history,” Father Justin says. In preserving their manuscripts, the monks of St. Catherine’s may also be preserving their way of life.